Peter Macken was born in Flanders, Belgium. After a successful career as a graphic designer and art director, his old passion, oil painting, reasserted itself. He devides his time between Antwerp and the Greek island of Paros, where he has lived on and off for the past fifteen years and where he has his painting studio. These ten works painted during 2020/21 are intended to be a visual reflection of how we deal with adversity.

How should we proceed, can we still escape, and what lies ahead? What started out as a meditation on Daedalus and the Icarus myth in Ovid’s Metamorphoses quickly morphed into something more contemporary. Always genuine, sometimes witty, often light-hearted, and frequently ‚tongue in cheek,‘ his paintings try to strike up a conversation with both ancient texts and contemporary poets.

Bruegel‘s vision lives on, not only in his celebrated works, but in the example he sets for succeeding painters to reinterpret his enduring concerns. He is an echo chamber. And as many people have discovered to their cost, pride comes before a fall and in the end life goes on whatever may happen.

The secondary sense of care is to be involved, to have empathy. A lifetime of talented design is complemented in this case by a mind stocked since youth with literature, and developed by having collections of great Flemish art on his doorstep to back up a rigorous art school training. But feeling is what gives art force, not just fluent technique (which is a test of artistic honesty) and his care for his fellow-beings is shown in this reimagining of the Icarus myth. Icarus was trying to reach out, to travel beyond the known, even to the skies to encounter the gods, just as those driven by misery, atrocity or the menace of death try to access countries that promise a more primary paradise, a life with food and work. As Icarus plunged from the clouds, they perish in the waves. The Icarus series tells us this quietly and intimately in the sky-diving or collapsed figures. The sequence says that for many of us the parachute does not open.

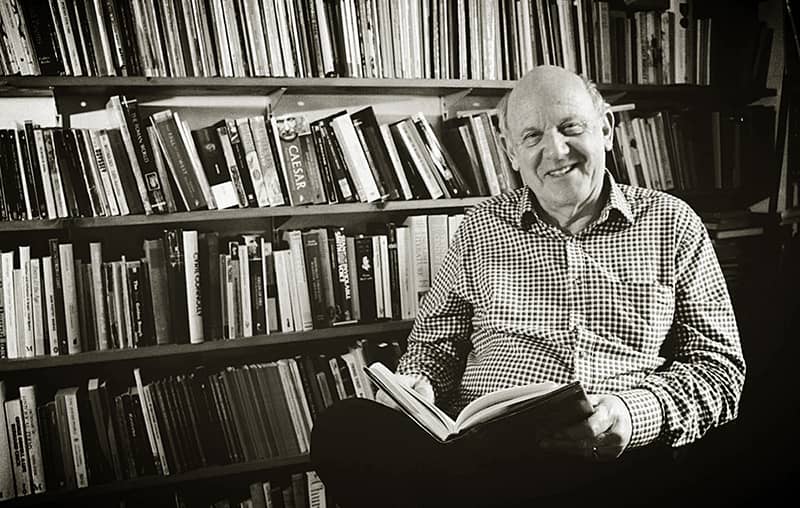

These paintings give pleasure above all. The storm-beset buoy is in a tradition of marine painting that portrays human resilience; the abandoned radio mast is Odysseus’s oar planted far inland; the portrait of an artist friend is a reincarnation of the master artificer Daedalus; the wild black dog that yelps and lurks is a single-headed Cerberus. These works are contemporary and timeless at once; yesterday is Troy, tomorrow another Fall of Rome as the missile-like columns in the Syracuse amphitheatre suggest. These paintings belong in quality galleries, then on the walls of private houses – but with one exception. The self-portrait staring out at a maze is the profoundly reflective work of a mature artist and is worthy of a public setting.

Rory Brennan

www.rorybrennanpoet.com